Faith, Freedom, and Fanaticism in the Middle East

Exclusive: A Washington, DC conference exposes the desires by Muslims and non-Muslims alike for a Middle East with freedom of speech and religion that many would only describe as a fantasy

By Andrew E. Harrod

(Washington, DC) Millions of Muslims “are looking for a way out of their misery,” Center for Democracy and Human Rights in Saudi Arabia (CDHR) President Executive Director Ali Alyami stated at a July 17 Washington, DC, panel. Yet the Saudi dissent Alyami’s discussion with his fellow panelists of the modern Middle East only emphasized how difficult an escape from this misery for Muslims and non-Muslims alike would be.

“I am not an expert in any religion,” Alyami confessed during an event held ideologically incongruously at the leftwing Institute for Policy Studies. (IPS Fellow Phyllis Bennis, a supporter of Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions or BDS against Israel, appeared in the adjacent kitchen during the panel.) But “Islam is not a faith; it is a way of life,” Alyami distinguished from other faiths, however comprehensive Christianity, for example, might have been in the past. “It is all God’s” in Islam in contrast to Jesus’ oft-cited separation between God and government (Caesar), Alyami elaborated.

“I like to think for myself,” Alyami stated in explaining how he personally drifted away from Islam’s encompassing embrace. Obedient to Islam’s daily schedule of five prayers beginning with a pre-dawn devotion, Alyami’s parents awakened him regularly at four a.m. Yet Alyami’s parents offered no good answer when asked why he could not pray to God according to a personal plan, an incident that led to lifelong questioning. Saudi Arabian religious authorities, he has condemned in a previous interview, “set themselves up as superior humans who must not only be worshiped, but fed by poverty-stricken people in the form of religious extortion: The Zakat system.”

Modern Muslims are emulating Alyami in unprecedented numbers, he argued, either calling for Islam’s enlightened reform or abandoning the faith altogether. Young Saudis, for example, spend more time viewing internet pornography than attending mosques. Accordingly, Alyami seeks dialogue with, not damnation of, violence-prone Muslims, even as he sometimes receives telephoned death threats. “You are being used as a tool,” he says to them, often prompting intellectual engagement. Although Muslim societies face a “bloody, long” revolution for freedom, Alyami remains optimistic of ultimate success. “The future will be bright for the Arabs” and others.

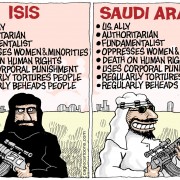

While discussing a decades-old “Saudi menace” supporting Islamic supremacism worldwide, though, Religious Freedom Coalition Chairman William J. Murray indicated significant barriers blocking a benign understanding of Islam. “No matter what good is done in the name of Islam, we always have the words of Muhammad to go back to,” words of Islam’s prophet whose import is often far from innocent. Evil done in Christianity’s name, by contrast, contradicts Jesus loving message. A moderate Muslim once claimed to Murray in Turkey that Islam has never had a reformer like Christianity’s Martin Luther. “Yes, you have had many,” Murray countered; “you have killed them all.” Muslims “almost need a Jesus Christ” who could fundamentally change Islam’s canons, rather than a reforming Luther, Murray argued.

Middle East Christians currently “have the pleasure of dying” under Islamic repression, meanwhile, according to International Christian Union (ICU) President Joseph Hakim in the audience. Hakim bemoaned considerable global Christian indifference today toward religious cleansing of Middle Eastern Christian communities. Yet the “Muslim world came like hawks” in reaction to atrocities against Bosnian Muslims in the 1990s.

An often “Christless church” is today “pro-Muslim and pro-gay at the same time,” Murray offered as explanation. “Mind-boggling” is also Grover Norquist’s continued prominence among conservatives despite his long association with nefarious Muslim individuals and George Soros-like leftist positions on issues such as homosexuality. Many conservatives would “flee” Norquist if “they truly understand what that guy represents.”

Christian communities had been forces for Middle East political moderation in the past, Murray argued, but now Hakim’s ICU associate, Steve Kressel, could only foresee “gathering up the remnants” of Christians in the region somewhere. Hakim in the past had proposed a sovereign Christian sanctuary in Lebanon along with other similar safe areas for communities such as the Druze. Such a Christian-majority polity in a Muslim-majority region would present parallels to the creation of Israel by Jews like Kressel. Though supportive of such a proposal, Alyami questioned how Middle East Christians could consolidate in one area.

Muslim “Sunni and Shia will slaughter each other” as well, as “Karbala is repeating itself” across the region, Hakim noted in reference to the central battle in Islam’s seventh-century sectarian division. Indicating centuries of regional sectarian hostility, the Lebanese Christian Hakim rejected describing the Middle East as “Arab.” After all, the region’s historic inhabitants such as Aramean-speakers only underwent Arab assimilation after a conquest emerging from the Arabian Peninsula.

Islamic fires of faith drove these events past and present, yet Alyami curiously has identified in the past Saudi Arabia’s “ruling elites” as the greatest obstacle to creating a Saudi Arabia promoted by the event without “religious orientation.” The “tragedy” that Saudi Arabia “prevents half of its society, women, from contributing to…their country” also “has nothing to do with religion or tradition, it’s political and economic,” Alyami has questionably asserted. Thus Alyami’s CDHR associate, panelist Jack Pierce, discussed buying off Saudi monarchy opposition to any free Saudi society with an oil-based trust fund.

“Most Muslims,” Alyami has nonetheless previously conceded, “believe that democracy American-style cannot work in Muslim countries.” Modification to the “religious and cultural heritage of Muslim societies” is necessary. Yet “CDHR promotes American-style democracy where the individuals, male or female, are in charge of their lives and destiny.”

Given Saudi Arabia’s “centrality to Islam” noted by Alyami in the past, though, Americanization presents significant challenges. Saudi rulers must consider both domestic and international Islamic opposition to any measures deemed un-Islamic from groups such as Al Qaeda or the Islamic State emerging to Saudi Arabia’s north, irrespective of actual sympathies. The 1979 overthrow of the Iranian Shah stands as a telling reminder in Saudi Arabia’s neighborhood of how Muslims can oppose Westernizing regimes with a zeal that does not require Saudi financing. Saudi Arabia’s rival, the Muslim Brotherhood (MB), suppressed both in Saudi Arabia and in Egypt by the Saudi-financed Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi regime, also shares Alyami’s support for working women in contrast to stricter Saudi Islamic interpretations. Yet this hardly makes MB-rule in Saudi Arabia or anywhere else acceptable to Alyami and likeminded supporters of equality before the law.

“Religious totalitarianism versus freedom of choice and the rule of law,” a “conflict of ideas,” is Alyami’s correctly identified challenge in Saudi Arabia and the Muslim world beyond. Not only must Alyami and others win this ideological battle, however, but they must do so with opponents perfectly willing to combine ideological with physical conflict. Alyami’s son, an Iraq veteran United States Army officer, personally attests this fact. Alyami’s way forward will be hard and long indeed.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!